You probably know that the Maryland Department of Transportation Maryland Port Administration is big. It is responsible for moving billions of dollars’ worth of cargo through its terminals every year. However, you might not know that it is also responsible for moving a lot of mud to keep navigation and shipping channels open. But before digging into the mud (pun intended), lets put this in context.

The Maryland Daily Record article, “Port of Baltimore an economic engine for the region,” identified the port as one of Maryland’s top economic generators – $59.7 billion total cargo value, $3 billion in personal wages and salary, and more than $300 million in state and local tax revenues. In the article, Don Fry, President and CEO of the Greater Baltimore Committee is quoted saying:

“The Port of Baltimore is an indispensable, if sometimes overlooked or taken for granted, economic jewel for the Baltimore region, and the state of Maryland. It’s not only one of the top employers statewide, but also is one of the pistons driving the economic engine of the entire Baltimore region.”

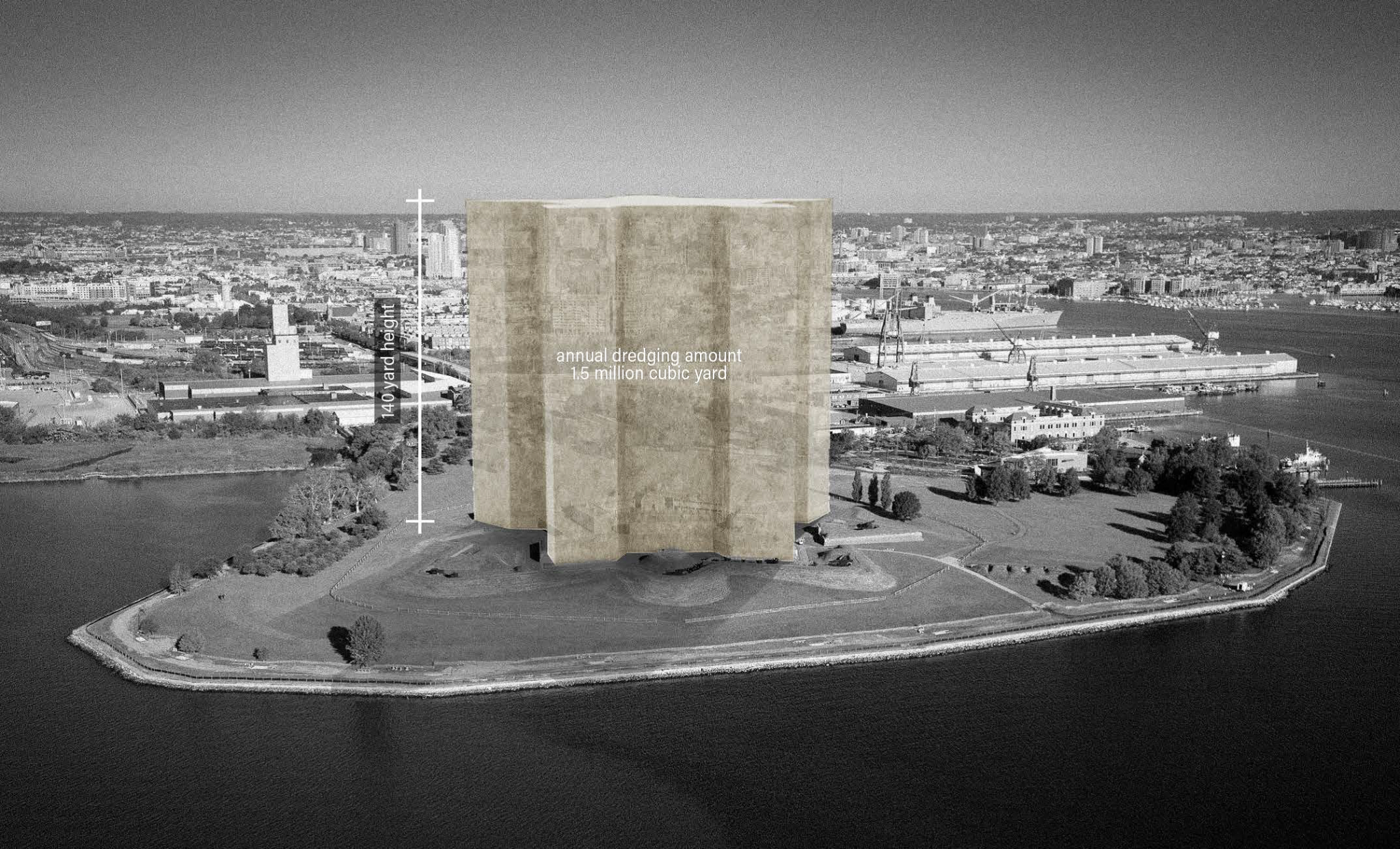

There is a lot at stake. With that in mind, imagine 1.5 million cubic yards of mud blocking the Port of Baltimore’s marine highway. It would grind shipping to a halt inthe mid-Atlantic. Need help visualizing this amount of mud? If you’ve ever visited Fort McHenry in Baltimore, envision the perimeter walls of the star fort rising 140 yards in the air filled with dirt. That’s the approximate amount of dredged material removed from the Baltimore harbor navigation channels every year (another 3 times that is taken from the federal navigation channels in the Chesapeake Bay). Where does it all go? And where will it go in the future?

These are the questions that MPA and Maryland’s Dredge Material Management Program must continually ask itself. Typically, dredged material goes to various containment facilities like the Masonville Dredged Material Containment Facility (DMCF), located in Anne Arundel County. Heard of Poplar Island, the bird and turtle refuge south of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge? What about that beach party your friend threw at Hart-Miller Island in Baltimore County?

Those are DMCF’s too. All filled with dredged sediment.

When feasible, the Port has beneficially reuses dredged material at places like the Paul S. Sarbanes Ecosystem Restoration Project at Poplar Island. However, while hugely successful, the Port and its stakeholders are looking for systemic strategies that address the challenges of regional sediment management that support navigation, as well as, environmental quality and quality of life in Maryland.

As landscape architects, urban designers, and planners, these are the kinds of questions we dream about answering at Mahan Rykiel Associates. We’re trained to weave together culture, economics, ecology, and aesthetics. So after our first tour of Port landscapes (terminals, DMCF’s, wetlands, etc.) we were hooked. Under the umbrella of our design research program, we pulled together a team of thought partners and began chewing on these issues in earnest. We developed a geospational suitability model to map and analyze opportunity sites across the region for beneficial use and innovative reuse of dredged material – exploring sites as diverse as rock quarries that might close in the next 20 years in need of repurposing and critical coastal habitat that might benefit from restoration?’ There were endless questions, with concrete challenges like cost, logistics, and social perceptions to be addressed, –— but also tremendous potential for regional resiliency and economic growth. During this study, our team was introduced to the Turner Station Conservation Teams, a community organization that has served on the Port’s advisory board, the Harbor Team for over a decade and has expressed support for new sediment management strategies.

That these ideas are not only being accepted, but also supported by the Turner Station community is a big deal. Turner Station is a historic African American community located along the Bear Creek tributary of the Patapsco River across from the old Bethlehem Steel Plant – now home to the global logistics hub Tradepoint Atlantic. In listening to the community, we learned about the ups and downs of living with industry as a bedfellow and how deeply rooted the community is not only to the land, but also to our nation’s history. They were the men and women who made the steel that helped our nation win WWII, and they were the families that made the ultimate sacrifice fighting in that war and those that have followed. They lifted up and were lifted up by industry through their blood, sweat, and tears, and now they are fighting to nurture and reclaim a community that has changed over the years as families have moved and new neighbors have settled in. You might be wondering how this relates to the Port or its mud, and in part of to the answer is Fleming Park, a 16-acre county park that was once a community hub, but that has fallen from its original glory after decades of impacts along the shoreline from highway construction to industrial pollution, to erosion and climate change.

What used to be a community hub with a beach where people would gather in the sun, a pier to go crabbing on, and picnic areas has become a place seldom visited for community functions (excluding the the activities of the Fleming Senior Center and the occasional pick-up basketball) game. The park is no longer the hub in Turner Station that it used to be—access and views to the water are now blocked by rampant growth of phragmites, an invasive wetland grass and what remains of the beach is strewn with construction debris and roadway trash. In recent years, the community has also suffered from more frequent flooding along its shores and streets. Could clean sediment dredged from the shipping channels be part of the answer?

The Turner Station Conservation Teams thinks so, and together with the community Mahan Rykiel has helped build a coalition of partners including the Chesapeake Bay Foundation and The Nature Conservancy who are working collaboratively to design, permit, and ultimately build a new waterfront park. The concept proposes utilizing maintenance channel dredged material to thicken the shoreline and create spaces that support a vibrant community of people, plants, and animals that are resilient and adaptive. However, more than a park, the community sees this as an opportunity to inspire pride in Turner Station and build the capacity of a new generation through dockside educational experiences and workforce development programs in coastal adaptation and green infrastructure.

With more than 7,000 miles of shoreline in the Maryland portion of the Chesapeake Bay projected to be effected by sea level rise in the coming years and the potential of dredged sediment to serve as a building block in coastal adaptation projects like Fleming Park, its easy to see the Port of Baltimore increasing in importance in the regional economy. Not only will it continue to drive cargo through its terminals, but also its sediment could fuel green infrastructure and construction industries helping to power habitat and reduce coastal flood risk. Of course, the jury is still out and we won’t know what’s truly possible until we prototype and pilot these new practices and evaluate project outcomes. However, the hard work has already begun and all the right people are around the table. We’re proud to be a part of this cooperative push and thankful for our partners in this work. It takes a village, but as we say here in Baltimore – team work makes the dream work.